Maureen Turim, “Popular Culture and the Comedy of Manners: Clueless and Fashion Clues,” in Jane Austen and Co.: Remaking the Past in Contemporary Culture edited by S. Young (New York and London: Routledge, 2007), pp. Rochelle Mabry, “About a Girl: Female Subjectivity and Sexuality in Contemporary Chick Culture,” in Chick Lit: the New Women’s Fiction edited by S. 292–296.ĭiane Negra “Structural Integrity, Historical Reversion, and the Post 9/11 Chick Flick,” Feminist Media Studies, 8:1 (2008), 51–68 Īlison Winch, “‘We Can Have It All”: The Girlfriend Flick,” Feminist Media Studies 12:1 (2012), 69–82 (71–5).įor more on the power of the beauty cult in France, see Mona Chollet, Beauté fatale: les nouveaux visages d’une alienation feminine (Paris: Zones, 2012) and Laure Mistral, La fabrique des filles: comment se reproduisent les stéréotypes et les discriminations sexuelles (Paris: Syros, 2010).įor details of the relatively high numbers of women film directors across the board in France since 2000, see Carrie Tarr, “Introduction: Women’s Filmmaking in France 2000–2010,” Studies in French Cinema 12:3, (2012), 189–200 (191).Ī. Jancovich (London: Bloomsbury, 2000), pp.

See Mary Harrod, “The réalisatrice and the rom-com in the 2000s,” Studies in French Cinema 12:3 (2012), 227–240.Ĭharlotte Brunsdon, “Post-feminism and Shopping Films,” in The Film Studies Reader edited by J. Young (New York and London: Routledge, 2008), pp. Mallory Young, “Chic flicks: the new European romance,” in Chick Flicks: Contemporary Women at the Movies edited by S. 1–25 ĭeborah Jermyn, Sex and the City (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2009), p. Negra (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2007), pp. Hilary Radner, Neo-Feminist Cinema: Girly Films, Chick Flicks, and Consumer Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 2010).ĭiane Negra, “‘Quality Postfeminism?’: Sex and the Single Girl on HBO,” Genders Online 39 (2004), Yvonne Tasker and Diane Negra “Introduction: Feminist Politics and Postfeminist Culture,” in Interrogating Postfeminism: Gender and the Politics of Popular Culture edited by Y. Other scholarly publications that have found the designation “chick-flick” to be a productive organizing category in various ways include Roberta Garrett, Postmodern Chick Flicks: The Return of the Woman’s Film (New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007) and It might be noted that my conception of chick-flicks as a generic category, albeit one that intersects with others, owes a debt to the new genre criticism of Richard Maltby, Steve Neale, and especially Rick Altman, who have emphasized film genres’ hybrid nature. Suzanne Ferriss and Mallory Young, “Introduction: Chick Flicks and Chick Culture,” in Chick Flicks: Contemporary Women at the Movies edited by S. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves. These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. Specifically, it argues that elements of the Anglo-American chick-flick-a term used by the popular press connoting female-focused narratives with an emphasis on traditional feminine concerns such as heterosexual romance, designed to appeal to a largely female-identified audience-have begun to be appropriated by filmmakers in different European contexts.

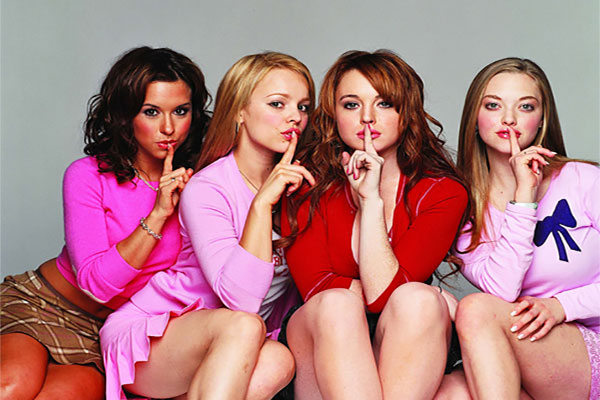

1 The starting point of this essay is the deracination of what I am calling “chick texts” at the point of production. For Ferriss and Young, “chick culture is vitally linked to postfeminism,” through an aesthetic defined by: “a return to femininity, the primacy of romantic attachments, girlpower, a focus on female pleasure and pleasures, and the value of consumer culture and girlie goods.” It can be seen as a collection of popular culture media forms principally concerned with middle-class women in their twenties and thirties, which are mostly American and British in origin. While postfeminism is often seen to succeed second-wave feminism in a neatly chronological way from the 1980s to today, the chick “cultural explosion” is located by Suzanne Ferriss and Mallory Young from the mid-1990s onwards, catalyzed for its most prominent theorists by the international success of the British novel Bridget Jones’s Diary (Helen Fielding, London: Picador, 1996). Anglo-American feminist film and television scholarship has of late been increasingly concerned with the negotiation by onscreen narratives of so-called postfeminist values, as well as their close cousin, “chick” culture.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)